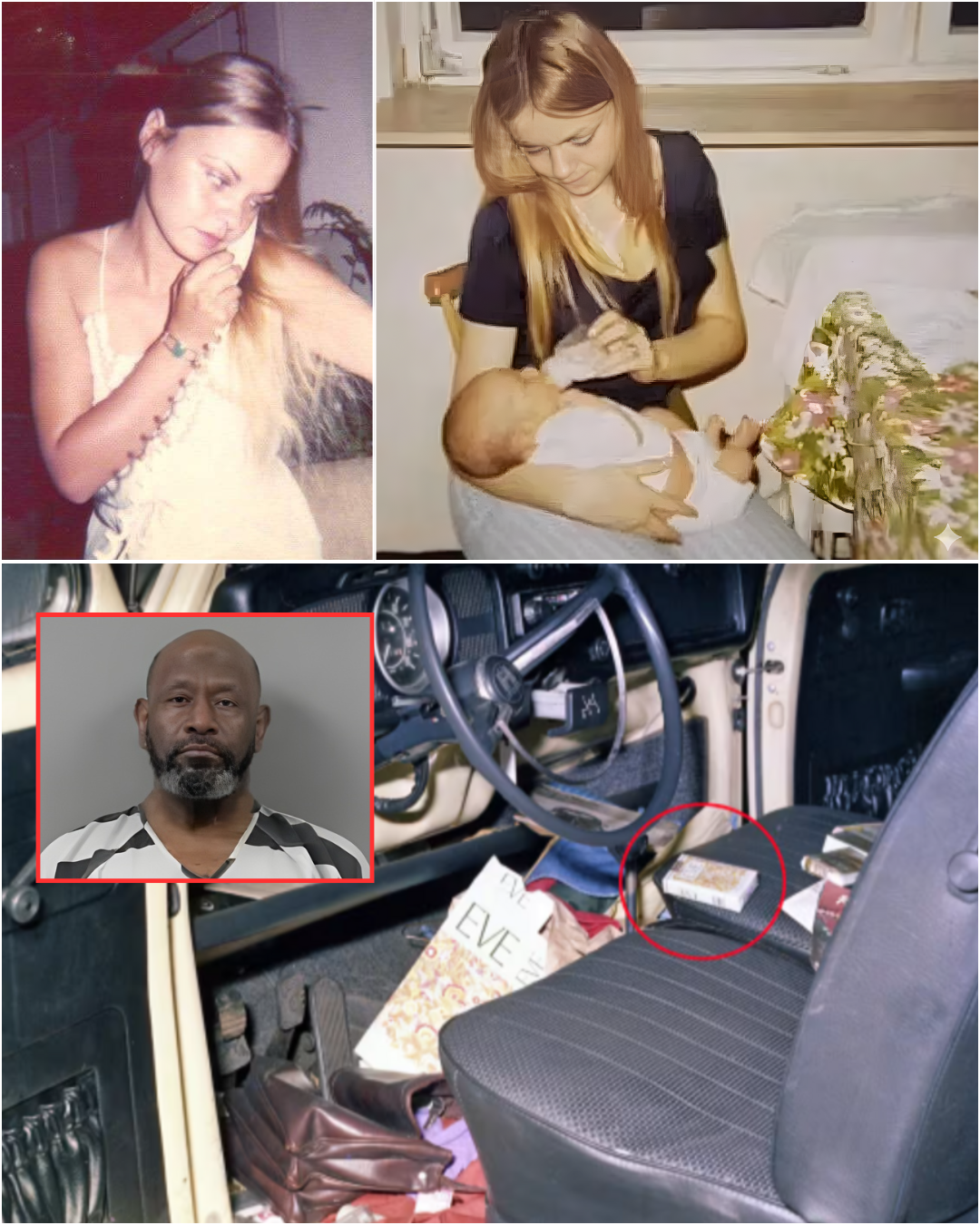

The bass was thumping through the walls of the Lion’s Den bar that January night in 1977, and Jeanette Ralston was laughing. Twenty-four years old, auburn hair catching the dim light, she had that kind of smile that made people feel warm inside. She’d left her six-year-old son, Allen, at home for the evening—just a girls’ night out in San Jose, California. Nothing special. Nothing out of the ordinary.

Until 11:50 PM.

That’s when she leaned across the table to her friends, her voice barely audible over the music.

“Ten minutes,” she said, nodding toward a man at the bar—someone they’d never seen before. “I’ll be right back”.

Her friends watched her walk toward the door with this stranger. They didn’t worry. Jeanette seemed relaxed, in control. Ten minutes. What could happen in ten minutes?

But when the clock struck midnight, Jeanette wasn’t back.

When the bar closed at 2 AM, she still hadn’t returned.

And when the sun rose over San Jose on February 1, 1977, police found her body crammed into the back seat of her Volkswagen Beetle, parked in a carport just three blocks from the Lion’s Den. A red shirt was twisted around her neck. The killer had tried to set the car on fire, but the little Beetle refused to burn.

Inside the car, detectives found a pack of Eve cigarettes—a brand marketed to women in the 1970s. It didn’t belong to Jeanette.

That cigarette pack would wait forty-eight years to tell its story.

The Boy Who Couldn’t Remember

Allen Ralston was six years old when his mother stopped coming home.

He has one memory that haunts him—sitting at the kitchen table, waiting. His father’s face. The relatives arriving. The hushed voices. And then, the slow realization that his mother wasn’t coming back.

Not today. Not tomorrow. Not ever.

For the next forty-eight years, Allen would grow up in the shadow of that absence. He went through childhood without her. Hit adolescence without her guidance. Became a man without ever really understanding the woman who gave him life.

He had photographs—just a few—but they felt more like artifacts from someone else’s life than actual memories. His mother’s face. Her smile. But he couldn’t remember her voice. Couldn’t remember what she smelled like when she hugged him. Couldn’t remember what it felt like to hear her say “I love you”.

May 2024 changed something.

His father handed him a manila envelope—old photographs Allen had never seen. His mother on the phone, laughing at something. His mother in the kitchen, mid-conversation. His mother alive, vibrant, caught in ordinary moments that would never be ordinary again.

Allen held those pictures and wept like he was six years old again.

What he didn’t know—what he couldn’t have known—was that at that exact moment, investigators were closing in on the man who killed her.

The Detective Who Wouldn’t Let Go

Deputy District Attorney Rob Baker has the kind of job that keeps you up at night.

He works cold cases for Santa Clara County—murders that happened before some of his colleagues were even born. Cases where witnesses are dying off, where evidence sits in storage rooms gathering dust, where families have given up hope.

The Jeanette Ralston case had been on his desk for years. He’d read the file so many times he could recite it from memory. The Lion’s Den bar. The cigarette pack. The fingerprints that matched no one. The DNA that sat preserved but unusable because 1977 technology couldn’t process it.

“This case haunted every prosecutor who touched it,” Baker would later say.

Here’s what made it so maddening: the 1977 detectives had done everything right. They’d lifted perfect fingerprints from that Eve cigarette pack. They’d collected DNA from under Jeanette’s fingernails—evidence she’d fought to preserve as she died. They’d interviewed witnesses, created composite sketches, followed every lead to dead ends.

But the fingerprints didn’t match anyone in the FBI’s database. Year after year, Baker and his predecessors would resubmit those prints, hoping the FBI’s database had grown large enough to include their killer.

Year after year: nothing.

In 2024, Baker decided to try one more time.

“Just about a year ago I was like, hey, let’s run those prints again to see if we get lucky,” he recalled.

August 2024.

The phone rang.

San Jose Police fingerprint analysts had news. After forty-eight years, they had a match.

The Thumbprint That Waited

Willie Eugene Sims.

That name meant nothing to anyone in 1977. He was twenty-one years old, an Army private stationed at Fort Ord in Monterey County, about seventy miles south of San Jose. Clean record. No arrests. No red flags.

But his thumb had been on that cigarette pack.

Here’s what happened: In 2018, the FBI upgraded its fingerprint database algorithm, making it more sophisticated—capable of finding matches that earlier systems had missed. The original investigators in 1977 had actually solved the case when they lifted that print. They just had to wait forty-eight years for technology to catch up.

When Baker got the call about the match, his first thought was verification. A fingerprint from 1977 was good, but after nearly half a century, he needed ironclad proof.

So he did what modern investigators do: he traveled to Ohio, where Willie Sims—now sixty-nine years old—had been living quietly for decades.

They collected a DNA sample.

Back in California, the Santa Clara County Crime Lab went to work. They compared Sims’ DNA to the evidence under Jeanette’s fingernails. They compared it to DNA on the red shirt used to strangle her.

Both matched.

“This was really an old-school resolution in many ways,” Baker would later remark. A fingerprint from 1977. DNA technology from 2025. The past and future of forensic science converging on one man.

Willie Eugene Sims.

The Soldier With Secrets

After Jeanette Ralston died, Willie Sims went back to his life.

One year later—1978—he was convicted of assault with intent to commit murder in Monterey County. A violent attack involving a knife. A jury found him guilty. He served four years in state prison.

But this was before CODIS—the federal DNA database. When Sims was released in the early 1980s, he moved to Ohio before California could collect his DNA. He started over. New state. Clean slate. No further criminal record.

For forty-eight years, he lived in Jefferson, Ohio. To his neighbors, he was probably just another older man—quiet, unremarkable. No one knew that in California, a cigarette pack in an evidence room held his secret.

Until May 6, 2025.

That’s when Ohio police knocked on his door.

The Phone Call That Changed Everything

Rob Baker had made difficult phone calls before. Telling families their loved ones’ cases had gone cold. Explaining that leads had dried up. Delivering news no one wants to hear.

But this call—this one to Allen Ralston in May 2025—was different.

Allen was about to turn fifty-four. Another birthday without his mother. Another year of questions with no answers.

“Allen, we got him,” Baker said.

The silence on the other end of the line lasted forever.

Then Allen Ralston—a fifty-four-year-old man who’d spent forty-eight years waiting—broke down and cried.

Later, he would describe the arrest as “a wonderful birthday gift”. Later, he would post on social media, his words addressed to Baker and every investigator who’d refused to give up: “You have undoubtedly made a 6-year-old kid happy after all these years. Thank you from the bottom of my heart on a job well done”.

That phrase—”6-year-old kid”—tells you everything you need to know about trauma.

Allen Ralston is fifty-four years old. But part of him has been frozen at age six since January 31, 1977. That’s the night his mother said “ten minutes” and never came back.

The Science That Caught A Killer

In 1977, DNA profiling didn’t exist.

Watson and Crick had discovered the structure of DNA in 1953, but it would take another three decades before that discovery could be applied to criminal investigation. British geneticist Sir Alec Jeffreys wouldn’t invent DNA profiling until 1984. The first criminal conviction using DNA evidence wouldn’t happen until 1987.

So when those 1977 detectives carefully collected biological evidence from under Jeanette Ralston’s fingernails, they were essentially sending a message to the future. They couldn’t analyze it. They couldn’t use it. But they preserved it anyway.

Forty-eight years later, that evidence spoke.

The Santa Clara County DA’s Crime Lab analyzed DNA that had been waiting in storage since the Carter administration. Degraded samples that would have been worthless in the 1990s could now yield complete genetic profiles in 2025.

The result? Willie Sims’ DNA matched evidence from Jeanette’s fingernails and the shirt used to strangle her.

Combined with the fingerprint on the cigarette pack, the case became bulletproof.

This breakthrough is part of a larger revolution sweeping America. Since 2018—when the Golden State Killer was caught using forensic genealogy—cold case units across the country have solved hundreds of decades-old murders.

Montana solved a double murder from 1956. Wake County, North Carolina closed a case from 1968. Arlington, Texas cracked a 1985 murder. Even in Santa Clara County, the same unit that solved Jeanette’s case used genealogy to identify Vivian Moss—a woman whose remains had been Jane Doe since 1981.

“Every day, forensic science grows better, and every day criminals are closer to being caught,” District Attorney Jeff Rosen declared. “Cases may grow old and be forgotten by the public. We don’t forget and we don’t give up”.

Since 2011, Santa Clara County’s Cold Case Unit has solved more than thirty murders. More than half were solved in just the last five years.

Technology isn’t just solving crimes—it’s rewriting justice.

The Witnesses Who Remembered

Here’s something remarkable: forty-eight years later, the witnesses who saw Jeanette leave the Lion’s Den bar with Willie Sims are still alive.

Think about that. In 1977, they were probably in their twenties or thirties. Now they’re in their seventies and eighties. They’ve lived entire lifetimes since that night. They’ve raised families, retired, watched the world change in ways that would have seemed impossible in 1977.

But they remember.

They remember Jeanette saying “ten minutes”. They remember the man she left with—his face, his demeanor. They helped create the composite sketch that went nowhere for decades.

When Willie Sims goes to trial, those witnesses will finally have their moment. They’ll tell a jury what they saw that January night. They’ll describe the last time they saw their friend alive.

“We’re very fortunate in this case that all of the key witnesses are still alive,” Baker explained. In cold cases spanning nearly half a century, that’s far from guaranteed.

It’s one more piece of an impossible puzzle that somehow came together.

The Cost Of Forty-Eight Years

While Willie Sims lived freely in Ohio, Allen Ralston grew up.

He went through first grade without his mother. Hit puberty without her. Graduated high school, went to college, got his first job, fell in love, had children of his own—all without her.

Every Mother’s Day was a wound. Every birthday a reminder. Every milestone where she should have been present—first day of school, graduation, his wedding, the birth of his own children—marked by her absence.

Jeanette’s parents—Allen’s grandparents—died without ever seeing justice for their daughter. The friends who were with her that night at the Lion’s Den carried the guilt of watching her leave. The 1977 detectives who worked the case retired without solving it.

This is the true cost of a cold case. Not just the unsolved crime, but the ripples across generations. The family that should have been but wasn’t. The memories that were never made. The love that was stolen.

“We can’t bring her back,” Rob Baker said with the brutal honesty of someone who’s worked dozens of these cases. “But we can answer a lot of the questions that the family may have had and try to get them some closure and hopefully justice in that way”.

On May 9, 2025, Willie Eugene Sims stood before a judge in San Jose. He was charged with murder. Held without bail. He did not enter a plea.

If convicted, he faces twenty-five years to life in prison. At sixty-nine years old, this essentially means he’ll die behind bars.

Some might say justice came too late. That Sims got away with murder for forty-eight years while Jeanette’s family suffered.

But ask Allen Ralston if he’d rather the case had remained unsolved. Ask him if knowing means nothing.

The answer is obvious.

Ten Minutes That Became Forever

“Ten minutes,” Jeanette Ralston said on January 31, 1977.

Those were among the last words she ever spoke. She thought she’d be right back. She had no idea that ten minutes would stretch into eternity.

But in another way, those ten minutes never ended. They extended through forty-eight years of investigation. They continued through Allen’s entire childhood, through his adolescence, through his adulthood. They persisted through technological revolutions, database expansions, relentless reanalysis.

They culminated in a fingerprint match in August 2024. A DNA confirmation in early 2025. An arrest in Ohio in May. And finally, answers.

Willie Eugene Sims.

That’s the answer to forty-eight years of questions. That’s whose thumbprint was on the cigarette pack. That’s whose DNA was under Jeanette’s fingernails as she fought for her life. That’s who strangled a twenty-four-year-old mother and left her in a Volkswagen Beetle, thinking he’d gotten away with it.

For forty-eight years, he was right.

But not anymore.

The Lion’s Den bar where Jeanette spent her last happy moments is gone now, replaced by office buildings in what became Silicon Valley. The San Jose of 1977—disco music and Volkswagen Beetles—has been transformed beyond recognition.

But some things haven’t changed.

The promise that we don’t forget. The commitment that we don’t give up. The certainty that justice, though delayed, will eventually arrive.

Allen Ralston is fifty-four years old now. He’s lived forty-eight years without his mother—longer than most people’s entire lives. He never got to know her as an adult. Never got to introduce her to his own children. Never got to say goodbye.

But he finally has something he didn’t have before.

He has answers.

He knows who took his mother away. He knows that person is being held accountable. He knows the investigators never stopped trying.

And that six-year-old boy, frozen in time since 1977, can finally start to heal.

The cigarette pack that sat in an evidence room for forty-eight years finally spoke.

And when it did, it told the truth.